I was recently having a conversation with a friend who likes architecture, in general, more than being a fan of modern architecture, specifically.

I was being my normal nerdy self and mentioned how when I get really attracted to a building, I want to touch its curves or edges. This is normally the part of the conversation where everything gets quiet and I realize I am alone in my feelings.

But to my surprise, he said, he knew exactly what I meant. He described a building at Harvard that was supported by a series of modernist columns that gently pushed outward as they descended the building. He and his future wife would walk there at night and lean against the columns and talk. He said you couldn’t be around them without wanting to touch them.

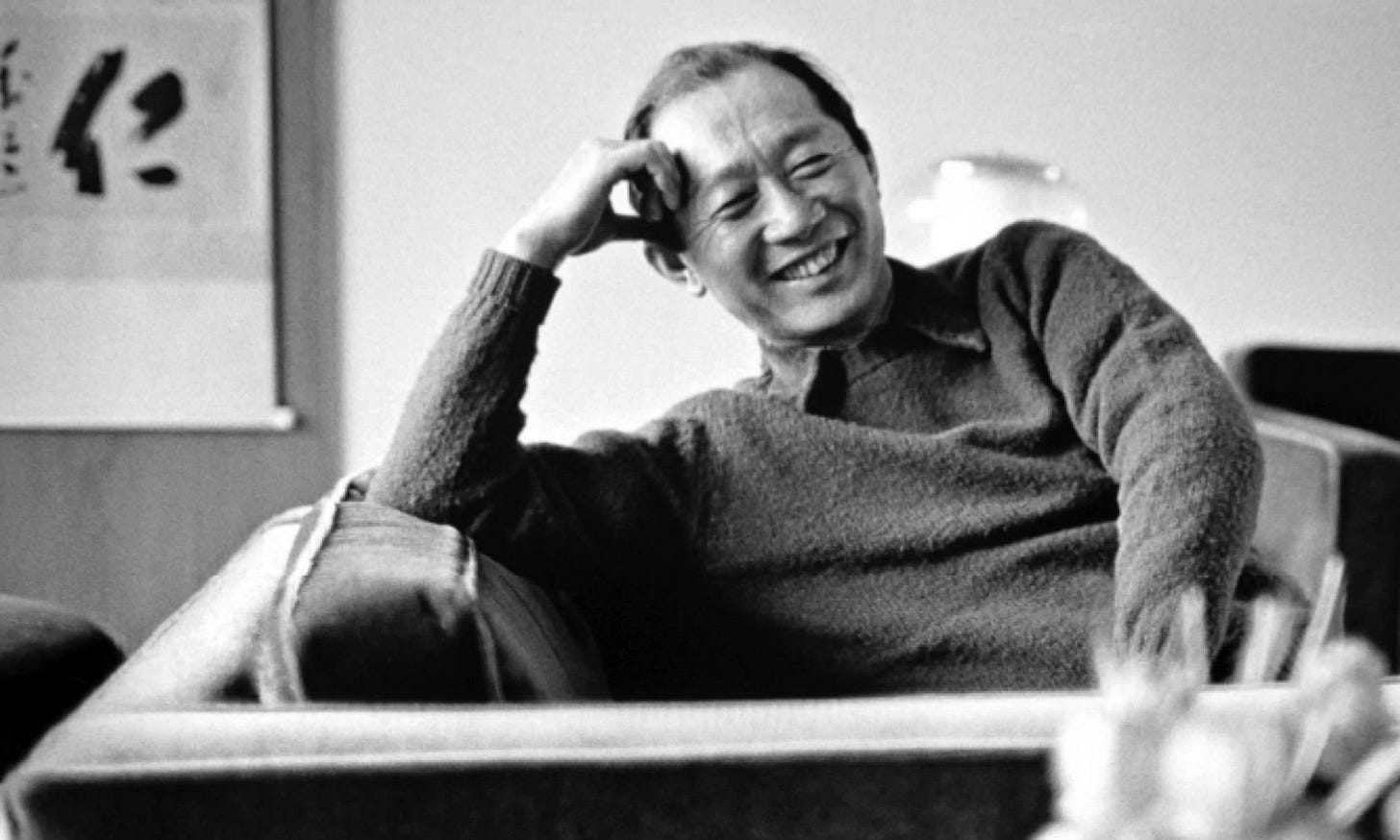

A little internet searching and we discovered it was Minoru Yamasaki’s William James Hall. I should have known it would be Yamasaki.

Yamasaki was put into the envelope of New Formalism architecture. In New Formalism, architects responded to the lack of historical reference in International Style architecture.

New Formalists used modernized columns most often in very official buildings. The grandeur of columns imparted the imagery that a government, bank, or insurance company wanted to portray.

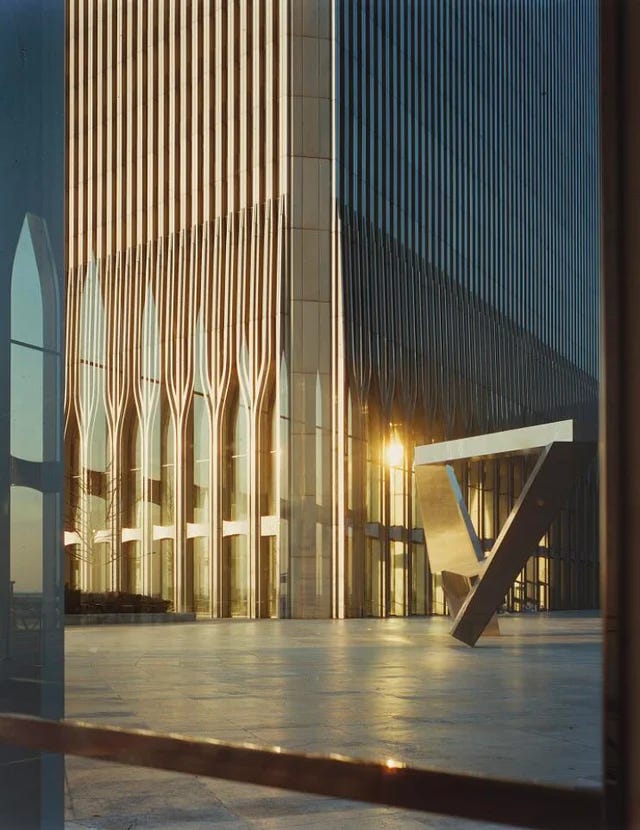

Look no further than the Northwestern National Life Building Yamasaki built in Minneapolis in 1965.

His sixty-three columns were made of concrete, but not like the brutalists who were obsessively being true to the color and texture of the medium. Yamasaki, and others of his style, painted the concrete white to resemble the Greek marble they were referring to. There was a grandeur to it that made underwriters and aluminum manufacturers happy.

Unfortunately, his most famous buildings are his most tragic. He won the commission for the World Trade Center building in 1962. Their physical monumentality almost make us forget that they were architecture. Their tragic history distort the rest of the record.

While not his most beautiful buildings, from lower elevations you can see his column motif and if you are lucky, you can look at them and just see buildings.

The World Trade Center and Yamasaki’s work, in general, was looked down upon by “serious” architecture thinkers. His ornamentation was viewed as frivolous to those who were looking to strip architecture of ornament (until the post-modernists became infatuated with the '“adorned box”).

Much of the criticism called his work “dainty, frilly, prissy, lacy”. All feminine related terms that cant be disconnected from the racism that Yamasaki saw throughout his life.

The child of Japanese immigrants, he worked up to 120 hours a week in summers canning salmon to pay for college. Only the architect that he worked for as a draftsman could protect him from the Internment Camps of WW2.

While he was best know for his “pillar” buildings, there were others that were more organic and fluid as well. Starting with his thin shell concrete work on the St Louis Lambert International Airport in 1955. Photo Balthazar Corab.

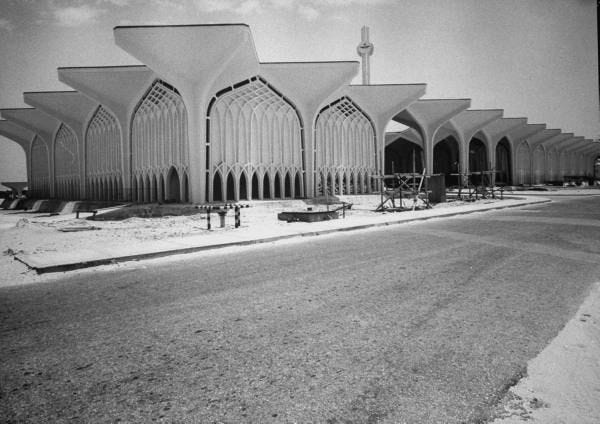

Then the Dhahran Terminal in Saudi Arabia in 1958 (Life Magazine).

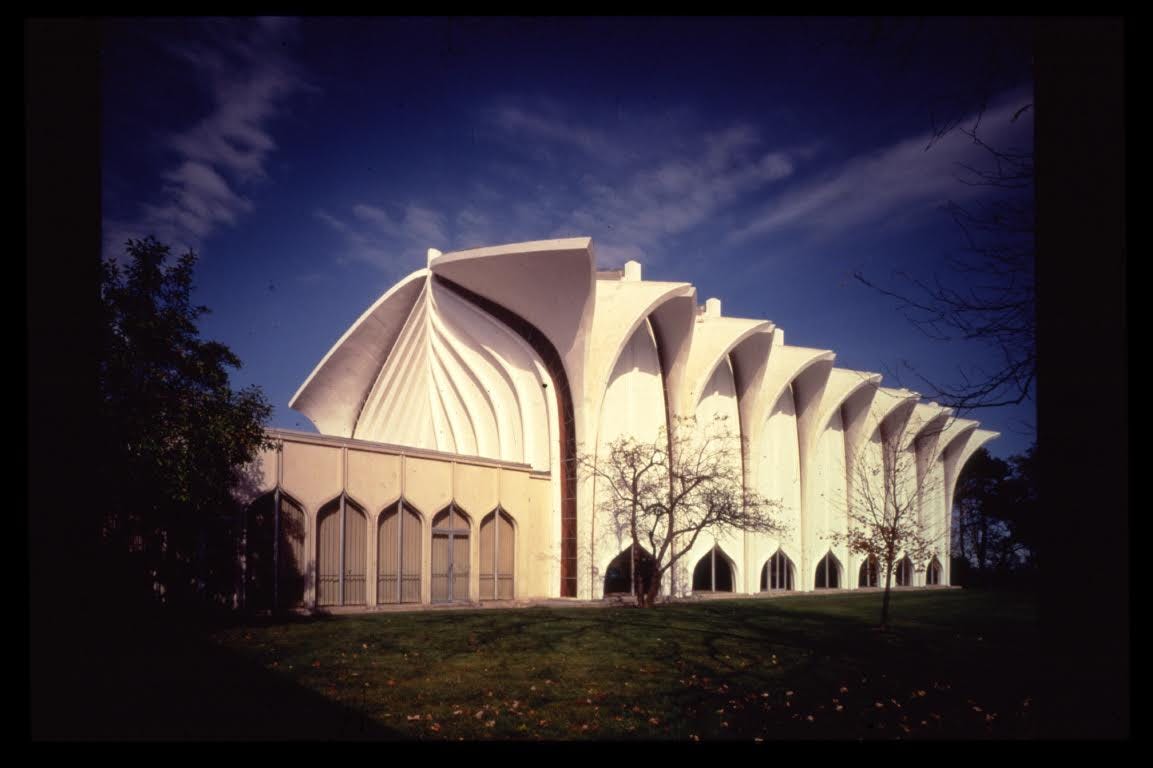

Also in 1958, the he made the lovely Willow Run Airport in Detroit (photo Balthazar Corab).

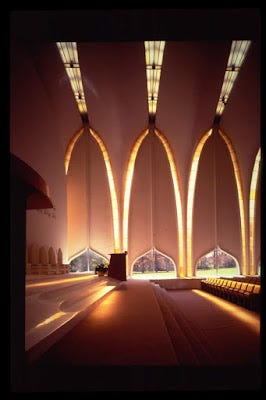

But maybe his most sinuous and organic was the North Shore Congregation Israel in 1964.

.

The exterior gives the impression somehow of whale-like shapes. The interior, in the same way, shows Joana’s view of the whale’s ribs.

Should I ever be so lucky to visit that Synagogue, I think I might be so inclined to reach out and touch.