Croatian architectural superstar, Boris Magas.

Boris Magas is not a common name in the United States. I only came across his work not too long ago. Unfortunately, with a few exceptions, there is seemingly a Eurocentrism to our (my) knowledge of architecture. We might know the Brazilian Oscar Niemeyer, who worked on the UN in New York, or maybe Mexico’s Luis Barragan, with his vivid pink and yellow fields of color.

Outside of that, most non-American architects people think of are French or German. Honestly, in my opinion, there are numerous architects on par with our Phillip Johnson, Paul Rudolph, or any European we consider great.

Look no further than Carlos Villaneuva of Venezuela, Francisco Artigas of Mexico, Eladio Dieste of Uruguay, Fruto Vivas of Venezuela, Kenneth Scott of Ghana, or Lina Bo Bardo of Brazil.

Or, in this case, Boris Magas. He was the leading Croatian modern architect for over fifty years until his death in 2013.

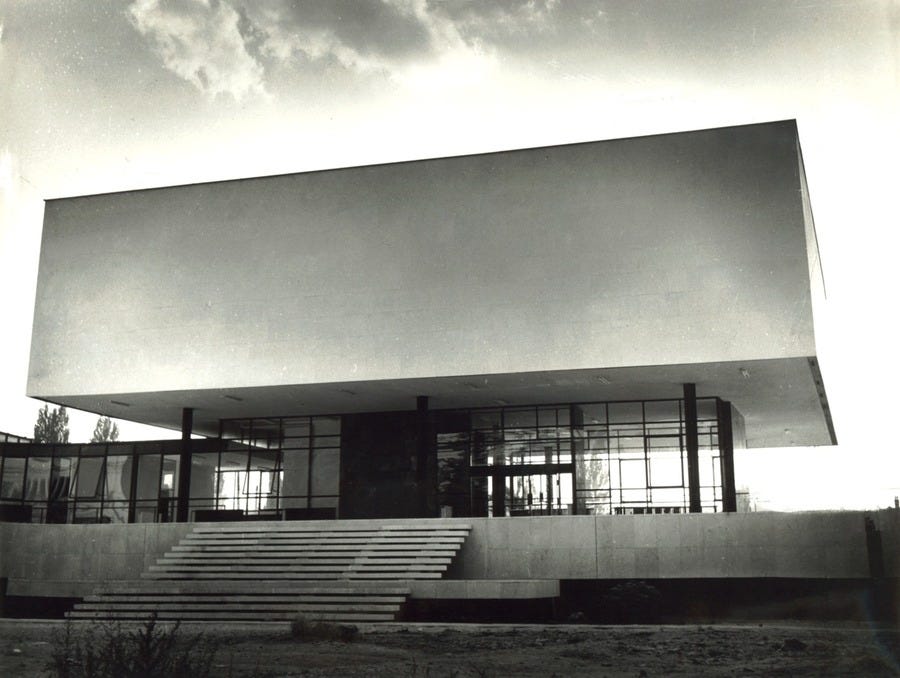

His first really substantial commission came at just twenty-eight years old when he was asked to design the Museum of the Revolution along with Edo Smidhen. What was produced was a superb example of International architectural style. The smooth marble form on top seems to levitate over the delicate structure beneath. The support is from just glass, steel, and a marble plinth. In some ways, this looks to have been informed by Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona Pavilion of 1929. You could be informed by worse.

While the building has fallen into some disrepair, appreciation for it is growing. In 2019, it was one of five buildings of Magas’ to be part of a Moma exhibit on Yugoslavian modern architecture. It has also acquired a commitment from the Getty Foundation to help maintain it.

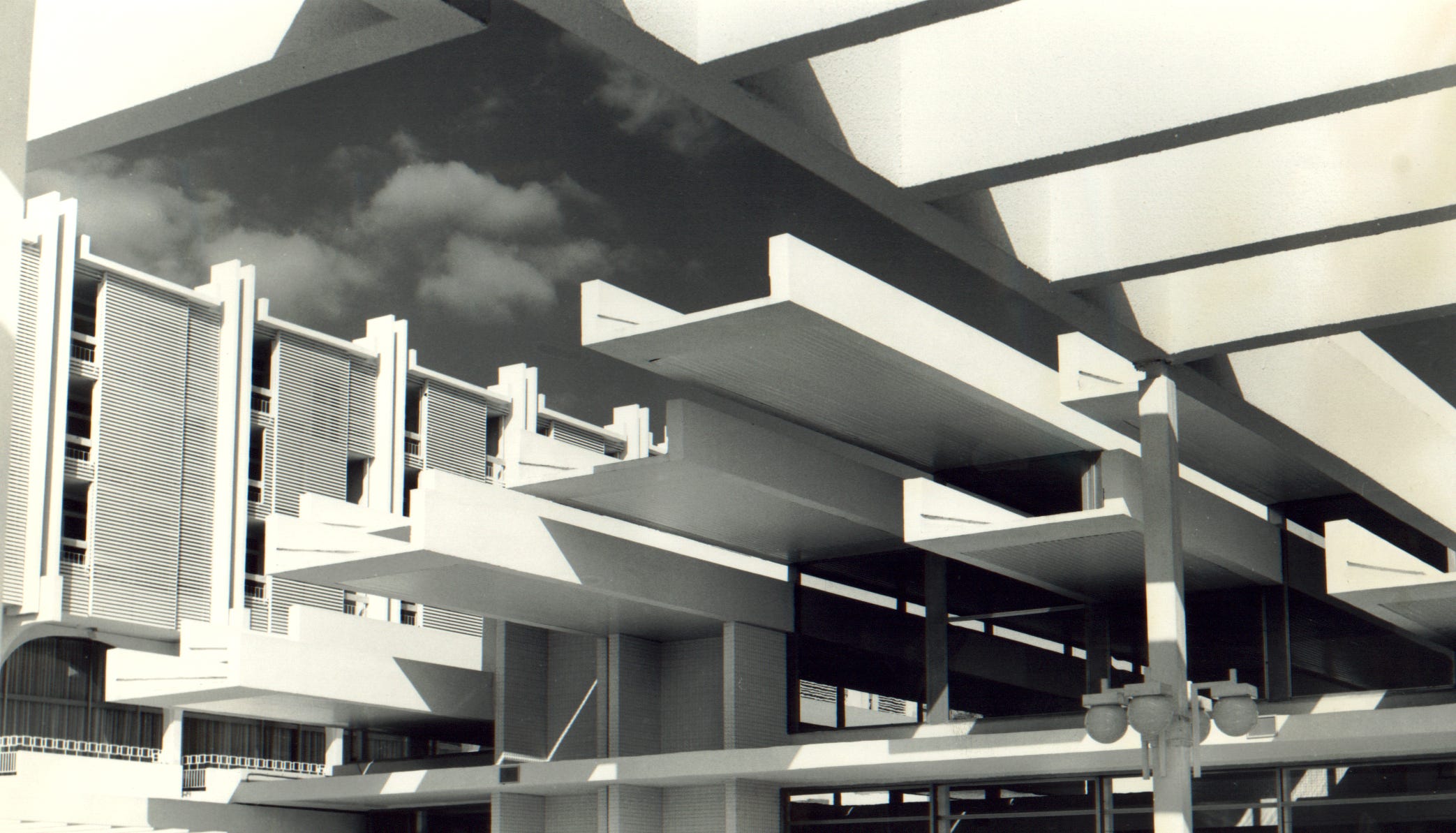

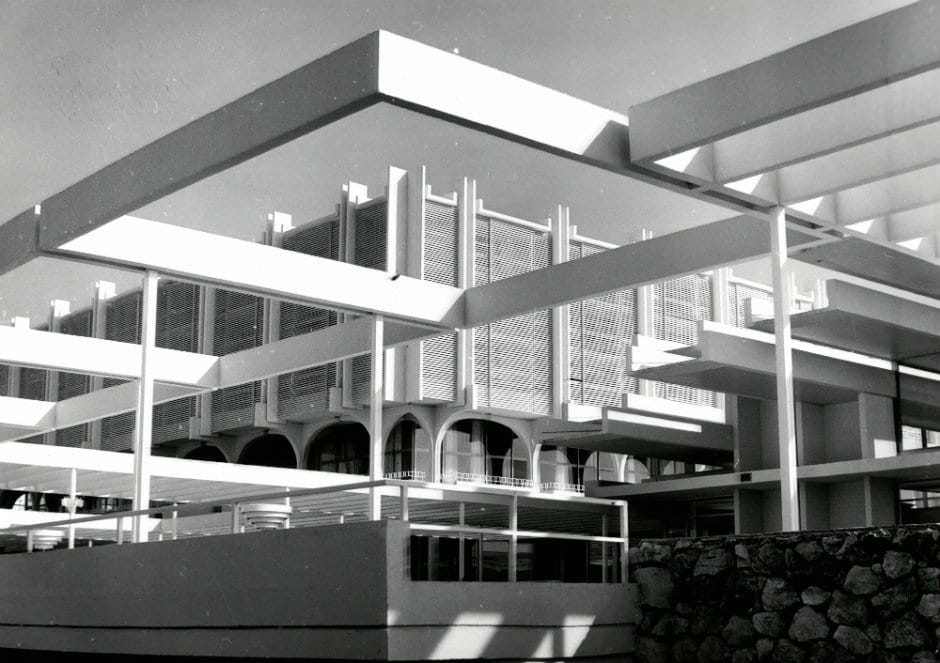

In the 1960’s he worked on multiple hotel-resort projects. In 1970, he took on an enormous project called the Haludovo Hotel, which was owned by Bob Guccione. It was the very picture of the kind of architecture you want to stare at while sitting by a pool, or playing a game of poker. Beautiful distraction.

Unfortunately, time has not been kind to the hotel, and it is now a destination for architecture students and those looking to photograph ruin porn.

Working for a more honorable purpose, in 1975 Magas produced the Mihaljevac Kindergarten and Nursery Centre in Zagreb. It showed how his style continued to change, from pure International at first, proto-seventies architectural glamor in the Haludovo, and now a new, angular style, continuing to move forward.

Magas was prolific, with over forty projects in his lifetime.

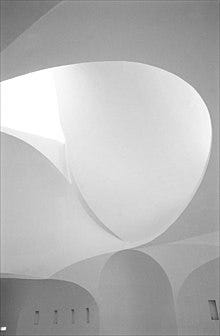

A later project that shows his continued ability to evolve was the Church of Augustina Kažotića, in Zagreb. Built in 1998, it was only a year after Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim in Bilbao. He would not have seen that building yet when designing the Church of Augustina Kažotića, not have known the impact of the flowing, sinuous structure.

But maybe responding to the same ideas and concepts, the Church of Augustina Kažotića flows inside like smoke from a votive candle.

Boris Magas is, again, one of many great architects who deserve our attention. Or, more realistically, one of the architects that we deserve to learn from and enjoy.